The Interview was conducted through email via an interview booklet and it is known as Digital Interview. Digital Interview defines how we connect through gaps and pauses in our contemporary period of technological renaissance as resources open up and anxiety takes over in the world of gadgets. Now we had come across Robert and his poetry last year when we published his poems in our inaugural April edition, 2017. Eight months later we thought of connecting the authors and readers when the interview space came like a proper thing to know each other. The interview is divided in several sections like a symphony and the tragic part is, it starts with the letters exchanged between us after the interview was finished and we would like to open the interview from the event like an interlude before going towards a prelude with our android message greetings, then with a tempo (short video capture), and finally a lead (interview booklet) towards a conclusion at the end. The whole interview utilizes each medium of our contemporary period, from text to image to audio to visual and hence with our inaugural session for interviews this year, we place before you our interview from The Quiet Letter with Robert Okaji.

I. The Interlude in Past

Hello Robert. How are you?

I am fine. And you?

I am fine. How is the weather?

At the moment it’s dry and cool. But this is Texas,

and things can quickly change.

Okay. What time is it?

11:00 a.m.

Are you busy with something?

I’m currently revising a manuscript,

in hopes of getting it in shape

to submit to publishers. It’s going slowly.

II. Tempo (Short Video Capture)

TQL: We shall start our interview with you, Robert. As you know it is a digital interview through Internet and also that it is narrative induced, opinionated, and interactive space where each has a separate role in forwarding the tone and the substance of our digital connection while allowing each other an open area of negotiation to place an emphasis on certain questions, while slightly neglecting others, and in overall manner, putting forward our best for the readers. Okay. Before that I would like to say your office is looking great. The books are lovely.

Robert Okaji: Thank you. It’s a small, but comfortable space dedicated to writing.

TQL: That is indeed great. Now we will start with the question zero and after which you can simply write down answers for the questions in the booklet as the video interview ends here now with this question.

RO: Yes.

TQL: Robert, what colour is your mental shelf?

RO: My mental shelf is like a lake – the color changes with the sky – shifting from bright blue to grey to midnight black depending upon life’s circumstances, mostly pertaining to what I’ve been reading (currently Turkish Poetry Today 2017), the background music (today, traditional shakuhachi tunes), and of course daily interaction with people.

III. Lead (Interview Booklet)

TQL: That is what makes you a Poet, Robert, but tell us what does it mean to be called as a poet when the term itself is excruciatingly understood by the writers themselves who are different from other types of artists? Why is it hard to understand poets?

RO: Yes, the term carries a lot of baggage with it, and I don’t concern myself much with which connotations others want to attach to it. I take “poet” at face value – one who writes poems. As for understanding poets, I believe that people often err in attempting to “understand” poetry and poets. It might be easier and more productive to ask how the poem makes you feel rather than what it means. The next question is, of course, why does this particular arrangement of words push those particular emotional buttons. Answering those questions might allow the reader to discover a personal meaning, which, to me, is much more important than what the poet intended.

TQL: You are right and I would like to say it is the reader who sifts through them to find an urgent meaning to his or her life. Now coming back to the process of writing, we would like to know how you write poems from Texas, United States. Is weather an amicable requirement for arrival of certain poems from the deep recess of your mind? We would like to know how a poem arrives, how it breathes, how it is seen at first sight, and how and why it is changed later?

Agave Root – @ Okaji’s Home

RO: Weather isn’t a requirement, but it certainly plays a role in much of what I write. In general, I sit down with absolutely no idea of what I’m going to write about. The weather occasionally frames the words – the way wind bends trees, or the sound of rain striking my shack’s metal roof. Of course I could say that about any external influence. My poems generally begin with a word or brief phrase, perhaps an image or simply a vague feeling. I jot down the word or phrase, or attempt to unearth the image or feeling. In other words, I seldom sit down with a preconceived notion of what will be written. It unfolds before me a word or phrase at a time. Sometimes the poems flow easily, sometimes they struggle to emerge. I don’t question the process, but just follow along. I revise as I write, but also like to let the poems lie fallow for a while, to “marinate.” The marination process may last a few days or even months, but when I look at the poems again, the errors or changes that need to be made are clear. This may be a matter of craft – line breaks, unintended repetitions, or form. Or it may seem that a certain portion is superfluous and needs to be deleted. This isn’t a quick process, but it works for me.

TQL:

Yes, it is the marination process which takes time and allow a poet to reconsider elements of language with a preciseness like a doctor of language, but your process is similar to what being a poet means even for me as a new poet because I have yet to take the test of marinating poems while they keep assembling themselves like a growth of wine on an electrical pole lying away on the roadside where I live, overlooking a farm and surrounded by orchards of genealogical inheritance of those who seem to like seeing the barbed-wires to not allow anyone to enter except women and men coming from marginal castes still have to find their way, wobbling themselves inside to pick a shade to rest for awhile, or to look at coconuts or mangoes as per the season. I have seen the fall of their kitsch sarees stuck in barbed-wires and I almost feel at times to run and wobble myself too to see what pleasure is it to take on the pain from centuries like an outsider. I want to hug them and I do so when my eyes meet theirs at times when I pass them but we have no language except brief chance dialogue. This could be the reason why I do not like to follow marination process for poems and prose in entirety except I believe in performing at once in a certain weather even if it brings along with it few errors of language because now after years of writing poems in my diary, meaning is becoming more important than syntactical or decorative aesthetic. If it is long then so it be with a deeper breathe that I take and if it is short then so be it like a gentle kiss on the lips of my beloved who lies in distance away from me. I suppose that is what makes each poet a different person in showing us the world as it is and I am glad you write from that distance as I write from here but let us not go there except it is a part of my process because I too have been working on novels which deal with certain thematic issues like I have discussed here, but that allows me to open our interview space more and that is why, Robert, when I tell you that you are the son of an immigrant to the United States, what do you think because I would like to know what does this mean to you and how does your poetry reflect this? Tell us about it.

RO: I have always carried a sense of otherness, of being different and perhaps never quite belonging. This manifests in my interests: in place, in ritual, in borders and gray areas, in the mundane and seldom noticed, and how one accommodates oneself — spiritually, physically, culturally, mentally, politically — in a climate that is not always welcoming to outsiders.

TQL: Thank you for the preciseness over my digression. I too have been an outsider in this society where my identity has been crumbled, distorted and misplaced by categorical infusion of caste and tribe while the issue of class keeps adding more problems for me and I can empathize with you. It allows me to see how education and its liberal culture has been always in the centre of urban spaces. Considering this, tell us about Poetry and Art scene in Texas. Do you go to poetry readings or seminars at public institutions? If so, what kind of experience you have had?

RO: Yes, now I haven’t experienced the Poetry and Art scenes in all of Texas, but from observation I’d say they’re most vibrant in larger urban areas, and almost non-existent in lower populated rural areas, with a few notable exceptions. I attend on occasion readings at public institutions and venues. They’ve almost always been enjoyable experiences, but I often get the feeling that some of the attendees and/or participants are there primarily to be seen, to become “known.” I must say that I prefer smaller, more intimate gatherings, perhaps a salon-type atmosphere at someone’s home, at which the audience is truly there to listen and participate. Those gatherings are, to me, much more genuine, more rewarding.

TQL: Yes it is so because such an intimate gathering always helps in being connected to the normal routine of life with other poets and readers. I think your experiences reverberate here too where divisions of urban and rural seems to have defined what a space of reading and engagement means and with what kind of education one arrives and how it is complemented in the real world, hence I would like to know, whether you are working currently on any poetry book project. I would also like you to briefly share with us, your education and life experiences.

RO: That is a good thing to say. As I mentioned earlier, I’m revising a full-length manuscript, but also have several completed chapbooks in the pipeline, searching for publishers, and am slowly writing a series of letter poems to various friends and writer acquaintances. Other than that, I try to write daily. My education is rather pedestrian: I hold an undergraduate degree in history and have never attended graduate school. But I’m curious and read a lot, and have been known to ask professor-poets for their syllabi or reading lists. My work life has varied over the decades – I served in the U.S. Navy for a short while, owned and managed a bookstore, and was an administrator at a university. All in all, I don’t possess the typical poet’s resume or credentials.

TQL: That means you have followed a non-traditional route towards educating yourself and I can relate to it as many of our readers will be able to relate to our contempoary period where digital publishing platforms like WordPress, Blogger, and Social Media Networking sites like Twitter and Facebook are useful platforms for a person to explore anything that is creative while not worrying about institutional support. The syllabus of highest order can be found through internet archives thanks to Aaron Schwartz. Yet there is a dilemma, because certain prominent publishing platforms such as magazines specify clearly that they do not want to entertain any piece of work that has been published before on blogs or other such services. A certain reality can be that they are unable to understand how such a medium is the only medium of learning for many and how they do not have wider readerships except fellow learners with them. How do you see such things when you submit your work to other magazines?

RO: I believe many newer poets are impatient and push out their work before it’s ready for publication. They’ve not read enough, haven’t put a sufficient amount of time and effort into the work, and the writing reflects that. But they submit, and then get depressed about rejection. This is part of the learning process, but frankly poets who are early in the process might think twice about submitting poetry to publications that publish well known poets. There’s a reason those poets are represented, and newer poets, who simply haven’t written enough, are seldom ready to compete at that level. Also, there’s a difference between posting a piece on one’s own blog and submitting a poem to a publication where an editor chooses what will be published. I don’t consider blog posts to be equivalent to or synonymous with publication, but some do. In my mind, publication requires an editorial hand, even if it is only to say no. Or perhaps especially to say no. Quite a few publications accept pieces from personal blogs, or even previously published work, so I don’t worry about whether something I post on the blog will ever be published. Either it will or it won’t. I know that by posting a poem I’m limiting the possibilities, but there are still many other opportunities out there.

TQL: Yes and that is why seeing you as an example by putting faith in such mediums allows me another question because you have published several chapbooks of poetry through traditional small publication press. Would you care to tell us how you went on to build a credible list with such marginal platforms while informing us about the readership that you get through these channels, the nature of such platforms who have been diligently helping new authors in their individual capacity with limited finances, the sign of personal growth as a poet, and lastly how you see the future of publishing in our contemporary digital world?

RO: I believe the publishing world as we know it is becoming more and more symbiotic. Publishers rely, at least in part, on their authors having already established audiences for their work. A publisher once told me that if he was considering two manuscripts of equal quality, and one had a vibrant online presence, he’d choose the writer with the online presence, because they’d be more likely to sell books. The blogo-sphere and social networking are crucial to this.

To be truthful, I’ve been methodical about publication. I asked myself what would enhance my chances, and came up with this brief list: a) write better poetry, b) find or create a readership/community, c) get individual poems published in as many journals as possible. To reach these goals, I attended a few workshops (helpful, but not essential), created my blog, “O at the Edges,” and began targeting publications, i.e. matching poems I’d written to publications that published the type of poetry I wrote (or thought I wrote). This all took time (nothing happened overnight), but it was time well spent.

My publishers are able to tap into an established readership based largely on my blog, and I, in turn, am able to distribute my poetry through the publisher’s channels – via the printed books being made available for sale, through their assistance in marketing and spreading the word to strangers, and with their personal and publishing contacts.

I like to think that the future of publishing is bright – that technology and art can and will combine forces to continue moving forward. When I first started writing, everything was done via snail mail. The internet didn’t exist, smartphones were only a dream. There was no digital world. Writers now have more publication opportunities and options than ever before, with more on the way.

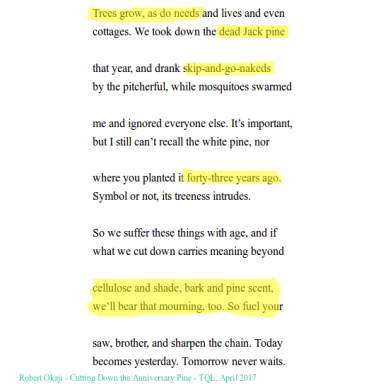

Second Part – Cutting Down the Anniversary Pine – TQL 2017

TQL: The technology, art and commerce can go hand in hand except there is a long way to see the future as bright and it should be bright in these times of chaotic network of information on the web. Now pausing here, I would like to take you to another space by evoking memories of my own experiences while trying to chart out a relation here. In Tokyo Story, Yasujiro shows contemporary Japan after the second world war with a subtle hint towards generational differences between young and old while exploring the meaning of warmth. kindness, loneliness, and aloofness through different characters as he does it with most of his movies which are different from his earlier work. He presents a humbled Japan trying to look at modernity while holding traditional beliefs which are rooted in natural world. In your poem, “Cutting Down the Anniversary Pine,” we could sense how spring, summer, winter, and autumn plays an important life and your poem resembles an earthy connection with earth while allowing a reader to experience sorrow. What led you to such a beautiful poem? Will you tell us how it germinated from a seed and expanded on to leave a meaning of time?

RO:

The genesis of this poem (and the others you published) is a bit unusual, in that they were drafted during a fund-raiser for Tupelo Press, in which 8 other poets and I were charged with raising funds by writing 30 poems in 30 days. One of the incentives I offered people, in hopes of enticing them to donate to the press, was to write poems to their titles. This particular title was sponsored by my brother-in-law, and I knew the story of the anniversary tree and have had a 30+ year relationship with him, so tapping into those histories established the poem’s parameters. The passage of time is of course crucial to the piece, as it is in many of my poems. We are such finite beings!

TQL: We are indeed but what about memory like this when you say, “If memory could speak, what would it not say? / Who else has rubbed this dust across his skin?” In this poem, Memory and Closets published in our inaugural April Edition in 2017, you unearth a picturesque memorabilia evoking objects that are lost and found again, which are of little importance except they last forever with us in our memories as writers, as poets. How did the poem arrive? What is memory for you Robert and how it is important for a poet to situate their being and contextualize life with larger ancestral and immediate societal environment in a constant flux?

RO: “Memory and Closets” was another sponsored poem, with the original title of “Cleaning Out Closets in Anticipation of Moving Closer to Children.” I chose an eclectic group of objects, some of which could be found in my house, others from imagination, with the hope of allowing readers to capture the sponsor’s intent and piece together their own stories from this grouping.

Poets have different focuses and means of extracting poems, so I can’t answer your question except from a personal angle: I can’t escape who and what I am, where I live, the various cultures and landscapes I’ve observed or participated in, the books I’ve read, the people encountered, the music and food sampled throughout a lifetime. They all contribute to whatever I produce, even if only in little nudges or micro-currents within larger pieces. I think it is important for poets to take notice of the world outside, to look beyond their personal lives. What they do with that is their choice.

TQL: We would like to hear a poem recited by you which is closer to your heart? (audio file)

RO: “A Word Bathing in Moonlight,” was published in Eclectica in summer 2017. The recording appears on my blog. The poem is:

A Word Bathing in Moonlight

You understand solitude,

the function of water,

how stones breathe

and the unbearable weight

of love. Give up, the voice says.

Trust only yourself.

Wrapped in light, you

turn outward. Burst forth.

TQL: That is a wonderful rendition, Robert and we thank you for providing it. This poem is a beautiful thought depicting forces of struggle and light. I like the texture it provides with the notion of solitude, water, and stone before opening the weight to say those words, Trust only yourself. Yet trust is what moves us as humans to belive in each other. Now moving over to the final two questions, we would like to know first, what is Education?

RO: Education is more than instruction, more than the accumulation of facts, skills and credentials. It is not simply memorization. It is a means by which we learn to analyze data, to draw together pieces of information, and reach theories or conclusions or suppositions. It is not black and white. It is not either/or. It is a constant state of learning, of seeking to learn. Education provides context, helps us frame questions. We should never stop questioning.

TQL: Thank you. Final question. What magical thing can you do for another person that would take no more than one minute of your life and which would change something in both for a lifetime to see?

RO: Sometimes a simple smile or greeting, an acknowledgment of another person’s humanity, can go a long way towards moving mountains.

TQL: Thank you. Have a great day.

RO: Thank you, you too have a great day.

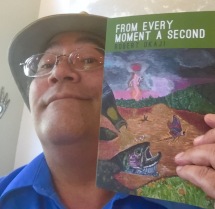

Robert Okaji’s work appears in Boston Review, Vox Populi, Posit, Silver Birch Press, Panoply and elsewhere. You can find chapbooks from Robert Okaji here:

- Origami Poems Project

- Interval’s Night

- From Every Moment a Second

- If Your Matter Could Reform

- The Circumference of Other (Ides: A Collection of Poetry Chapbooks).

An excellent interview of my favorite poet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank You, Wright. Best from The Quiet Letter.

LikeLike

Wonderful interview – thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jazz. Your name is lovely too.

Regards

The Quiet Letter Team

LikeLiked by 1 person